San Clemente Dam

An Environmental Topics summary by the ENVS 560/L Watershed Systems class at CSUMB.

This page gives a short history of the former San Clemente Dam, a description of the completed dam removal project, its environmental impact, and post-construction monitoring efforts. As of 2017, the project ranked as the largest dam removal project in California history.[1]

History

The San Clemente Dam was built in 1921 by a local businessman Samuel Morse on the Carmel River to supply the water needs of Monterey's growing population and tourism industry. Due to sedimentation, threats to federally listed species, and seismic safety issues, the dam was removed and the Carmel River was rerouted at the former dam site in 2016.[1]

In 1930, Morse sold the dam to Chester Loveland, who owned the California Water and Telephone Company (CW&T). To meet the needs of the growing population and increasing demand from the sardine processing industry in Monterey, CW&T built the Los Padres Dam upstream from San Clemente Dam in 1948.[2] In 1966 CW&T sold the San Clemente Dam to California American Water Company (CalAm) for $42 million. [3].

Dam Removal

In 2013 the San Clemente Dam was commissioned to be removed. Granite Construction, a locally-based construction management firm, served as the general contractor for the dam removal. Before the dam was taken down, they worked for two years to prepare the site by rerouting the river and relocating reservoir sediments. The San Clemente Dam was removed in the summer of 2015.[4]

Reasons for Dam Removal

Geology and Sedimentation

The former San Clemente Dam site is surrounded by steep slopes of fractured granite that are subject to severe erosion during heavy precipitation events (Image 2). In addition, the rugged terrain and arid climate of the Santa Lucia Mountains make wildfires difficult to control, leading to a range of land and water management challenges in the wake of fire. Numerous local wildfires contributed substantially to a decrease in reservoir capacity at the San Clemente Dam site.[5] By 2002, the dam was no longer supplying water due to sedimentation[6] By 2012, 98% of its original capacity was lost to sedimentation, making the dam a potential safety hazard.[3]

Threatened Species

There are two, federally-listed species in the Carmel River Watershed that would likely benefit from a restored river in place of the dam.

- The Central Coast Steelhead trout population, endemic to the Carmel River, is within the South-Central California Coast (SCCC) Evolutionarily Significant Unit (ESU). The SCCC ESU has been classified as "threatened". The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) is responsible for managing and maintaining a healthy steelhead population and is working on restoration of the population to historic levels in the Carmel River.[7] The declining population of Central Coast Steelhead in the Carmel River was deemed a result of partial barriers to spawning and rearing habitat created in part by the Los Padres Dam, San Clemente Dam, and Old Carmel River Dam.

- The California Red-legged frog was listed as threatened in 1996 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The California Red-legged frog is found in different parts of the watershed. The health of its population is unclear. Development and water extraction activities have required additional review to ensure its habitat within the Carmel River is in compliance with the Endangered Species Act (ESA) (ESA).[8]

Seismic Considerations

Located near the Cachagua and Tularcitos faults,[9] the San Clemente Dam was deemed vulnerable to a catastrophic failure in the event of a maximum credible earthquake or probable maximum flood and was listed in the 1990s as a high priority public safety issue by the California Department of Water Resources(DWR) Division of Safety of Dams (DSOD). With the dam having reached the end of its expected useful life and 1500 homes and other structures below the dam under threat, in 2006 the DWR released a Draft Environmental Impact Report/Environmental Impact Statement (EIR/EIS) exploring options to mitigate safety hazards through either dam removal or dam reinforcement. While CalAm proposed reinforcing the dam to mitigate safety hazards, other stakeholders including the NOAA Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) advocated removal in order to benefit local Steelhead, subject to population decline. The EIR explored CalAm's preferred option of strengthening the Dam and four alternative projects, including the Carmel River Reroute and Dam Removal (CRRDR) option. The CRRDR option had several ecological benefits that the Dam Strengthening option did not. In 2008, the DSOD stated that the CRRDR project would address the dam's public safety and environmental impact issues, making it the best option for all stakeholders.

Carmel River Reroute and Dam Removal (CRRDR) Project:

The Carmel River Reroute and Dam Removal (CRRDR) was expected to provide several benefits for the Carmel River including:

- Permanent resolution to the dam's safety concern

- Access to 25+ miles of spawning and rearing habitat for Steelhead trout

- California Red-legged frog habitat improvement

- Restoration of sediment to the downstream reach of the river and Carmel River State Beach

- Restored ecological connectivity for riparian and aquatic habitats.[10]

Project Details

Before any work on the project was performed, the County of Monterey drafted a document for CalAm that covered all requirements for the dam removal project, including sediment, vegetation, municipal, and biological monitoring.[11]

In order to carry out the CRRDR in 2013, access roads were constructed off of Carmel Valley Road after Carmel Valley Village and before the Sleepy Hollow turn-off.

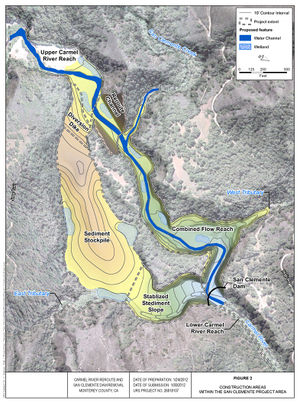

The Carmel River was rerouted into the adjacent San Clemente Creek, a half mile upstream of the dam, by cutting a diversion channel through a narrow ridge separating the two channels. The rock excavated during construction of the diversion channel was used to block off the sedimented reach of the Carmel above the dam and is referred to as the diversion dike (Image 3). The sediment that had accumulated in the channel directly behind the dam was excavated and transferred to the upper portion of the Carmel reach and stabilized to prevent erosion during high flows (Image 3).

The reach of San Clemente Creek downstream of the diversion dike was converted to a system of step pools. The restoration was intended to create a riparian corridor that included seasonal ponds for California Red-legged frog habitat. In 2014, the San Clemente Dam and fish ladder was removed. Once removed, the Old Carmel River Dam (1800 ft downstream) was also removed to improve Steelhead passage and overall river stability.

The eventual plan is for CalAm to transfer the completed project to the Monterey Peninsula Regional Park District. Adding this portion of land to the Park District will link Garland Regional Park and the San Clemente Open Space. The property use will be restricted for watershed conservation and compatible public access [12].

The total cost of the project was 83 million dollars. CalAm contributed 49 million dollars, the original cost to stabilize the dam in-place. The remaining funds were contributed by numerous other agencies such as California State Coastal Conservancy (Conservancy), NMFS, and the Planning and Conservation League Foundation.

Project Details from Agreements

CalAm was held to standards and timelines set by an agreement for the CRDDR written by the CDFW in 2013. The agreement was amended in 2015 and 2016 to allow more habitat restoration in and around the dam removal site in all seasons[13]. The 2013 standards included:

- Notifying the CDFW of any special status species that were present during construction or prior to construction[13]

- Removing of any invasive species, such as American Bullfrog and Red Swamp Crawfish[13]

- Replenishing the local tree species (i.e., Willows, White Alder, etc.) with exact numbers specified by the CDFW agreement[13]

- Reporting sightings of the nests from Bald Eagles and Dusky-Footed Woodrats along with surveys of nesting birds and roosting bats within 30 days of the sightings and surveys[13]

- Following all permitted standards and regulations

Removal Timeline

Below are the key project goals from 2013 to 2016. The project was completed on schedule in 2016.

2013

- Access road design and construct

- Finalized diversion system design

- Obtain permits and government approval

- Wildlife relocation along new Access Road and Project Site

- Site preparation including clearing, fencing, and construction access roads

- Geotechnical investigations111

- Partial construction of Diversion System

2014

- Site earthwork design

- Complete construction of Diversion System

- Construct Diversion Dike

- Construct the Re-Route Channel

- Construct the Sediment Stockpile

- Partial excavation of the Combined Flow Reach

- Partial San Clemente Dam removal

- Additional geotechnical investigation

2015

- Construct the Stabilized Sediment Slope

- Finalize Channel and Habitat restoration design

- Complete demolition of the San Clemente Dam

- Construction of the Combined Flow Reach Channel

- Initial habitat restoration

- Construct permanent bridge over Carmel River

2016

- Completion of habitat restoration & irrigation system

- Removal of the Old Carmel River Dam

- Construct the Sleepy Hollow Ford Bridge

- Start of monitoring and habitat establishment periods

Project Status

Heavy precipitation events in the wake of the Soberanes Fire, during the winter of water-year 2017, caused extreme flood events that completely rearranged the 54 engineered step pools in the San Clemente River reroute channel.[14] The step-pool system has not been reconstructed. These high flows also resulted in sediment from the former San Clemente Dam reservoir being transported throughout the course of the Carmel River, with significant aggradation and pool filling found as far downstream as the river mouth. [15]

Post-Removal

Post-Removal Monitoring

Several post-dam removal monitoring criteria are established in the Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program (MMRP).[16] These monitoring and mitigation criteria are the responsibility of CalAm and their contractors, and fall into the categories of:

- Geology and soils

- Hydrology and water resources

- Water quality

- Fisheries

- Vegetation and wildlife

- Wetlands

- Air quality

- Greenhouse gas emissions

- Noise

- Traffic and circulation

- Cultural resources

- Visual Resources

- Recreation.

Some scientists involved gave more detailed information on the processes of post-construction monitoring[17]. These include:

- Between 5 and 10 years of post construction monitoring

- Before-After-Control-Impact (BACI) studies by NMFS and Southwest Fisheries Science Center (SWSFC)

- Total suspended solids (TSS) monitoring by the United States Geologic Survey (USGS)

- Channel Morphology monitoring by CSUMB

- Redd (fish spawning) surveys by the Monterey Peninsula Water Management District (MPWMD)

- Benthic Macroinvertebrate sampling by MPWMD and Granite Construction

- Steelhead counts above and below the removal by CalAm/MPWMD

- Potential Passive Integrative Transporter (PIT) tagging by a collaboration with CSUMB, NMFS and MPWMD

Broad themes of post-construction monitoring efforts were made known to the public, but most were kept private until recently. Some of these broad themes included:

- Fish passage studies by California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB) and AECOM[18][19]

- Morphological Monitoring of the Carmel River Channel by California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB)[20][21][22] and by Harrison et al.[15]

- Large Woody Debris on the Carmel River From Camp Steffani Road to the Carmel Lagoon by California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB) [23] [24]

Permitting for Post-Removal Monitoring

Recently, documents such as agreements, permits, and post-monitoring reports were made public. The following two sections are a summary of these documents[25]:

CalAm had to adhere to guidelines and restrictions in geotechnical, vegetation, biological, and hydrological permits[25] distributed in 2013 by:[26]

- The United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)

- The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW)

- The Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB)

- The United States Fish and Wildlife Services (USFWS)

- The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS)

- The United States Environmental Protection Agency

- The Department of Water Resources

- Monterey County

Permits[25] granted for the dam removal stated that geomorphological, California Red-legged frog, Steelhead, and vegetation monitoring would have to be conducted 1, 2, 3, and 5[11] years after the removal of the dam (10 years was also stated in the project description "if needed")[26]. Permits also stated that annual reports must be written for every year of monitoring, and the final year (5 or 10) must include all information to that date, and describe how all permitting processes were met[11]. Granite construction also underwent a permitting process for removal of concrete and alteration of the geomorphology of the Carmel River, most of which were distributed in 2014[27]. The State Coastal Conservancy Executive Officer, Samuel Shuchat, granted CalAm a total of $32,827,403.64 for the implementation of the San Clemente Dam Removal, via a formal agreement (appended nine times) [28].

Post-Removal Efforts

AECOM released its "Year 1" post-construction monitoring report of geomorphological,Steelhead, and California Red-legged frog surveys for CalAm in February 2019. AECOM's "Year 1" reports for geotechnological and re-vegetation monitoring were prepared for CalAm in December 2018. Year 1 reports can be found here.[29] Some of the post-removal monitoring efforts, which were defined in the agreements and permits[25], included:

- No net loss of wetland habitat (set by the United States Army Corps of Engineers Section 404 permit signed by AECOM)[26]

- Ensuring survival rates no less than 70% and 50% (stated in the Habitat MMRP and the CDFW permits, respectively) of protected tree species in the riparian and upland areas [26]

- Replace permit-specified numbers of protected tree species in the riparian and upland areas [26]

Trends of MPWMD Monitoring

MPWMD focused on mainly biologic (i.e., Steelhead and riparian vegetation) surveys. They have monitored the Carmel River for over a decade. All MPWMD publicly available monitoring reports (including the most recent post-removal monitoring report) with summaries of results can be found here[30].

Trends for some of the reports were:

- The 2000-2001 annual report stated that adult Steelhead populations had increased from "a handful" to almost 900 recorded individuals[31] and that riparian corridor vegetation improved[31]

- In 2002-2003, adult Steelhead were counted, while 16,238 juveniles were rescued from drying areas. Six hundred tons of gravel were set to create suitable breeding grounds for Steelhead[32]

- in 2003-2004, 388 adult Steelhead were counted and 50,277 smolts were rescued. CalAm and MPWMD experimented new ways to plant riparian vegetation to efficiently use irrigation. Effects of woody debris were also inspected in the Carmel River[33]

- Fewer adults and juvenile Steelhead were counted (328 and 6,124, respectively) in 2004-2005. Bioassessment protocols were performed at 6 locations in the Carmel River. Riparian vegetation was reported to be healthy, which was thought to be caused by the decrease in fine sediments upstream[34]

- Steelhead were recovering from their low numbers, but the recovery was only increasing slightly (368 adults). The channel was recorded to be recovering from its widened state after floods in the late 1990s, likely due to riparian and channel vegetation stabilizing the banks[35]

- Flows dropped to 0 cfs near the Highway 1 bridge and stayed below 10 cfs until May of 2007. Steelhead numbers were very low and small numbers of smolts were let out to the ocean via the river mouth, which was manually opened after going dry. The monitoring program continued its efforts to plant riparian and channel vegetation in a way to reduce its reliance on irrigation and filled exposed banks with vegetation to mitigate erosion. Two property owners were also charged for "serious violations" of standards set in 2003[36]

- Steelhead numbers were higher in 2007-2008 than the previous year's report, resulting in 17 adults, approximately 12,000 juveniles, 38 of which died upon rescue. The two property owners from 2006-2007 were continually prosecuted. The rip-rap they installed was removed and they were no longer allowed to perform work without a proper permit [37]

- The 2016-2017 post-removal report stated that flow was extremely low in some areas of the Carmel River (less than 10 cfs), which forced daily monitoring to occur. A total of 670 Steelhead were counted, including 425 juveniles. Additional vegetation was planted to account for erosion, which was a main protocol for this annual monitoring[38]

- Surface flow fell to less than 10 cfs in some reaches of the river in the summer of 2018, causing the need for daily monitoring. Fish rescues in the mainstem Carmel River yielded a total of 2,794 Steelhead (1,396 young-of-the-year (YOY) and 1,383 yearlings). Tributary rescue totals reached 2,164 Steelhead (1,855 YOY and 295 yearlings). Of the 4,958 Steelhead rescued from both the mainstem river and tributaries, there were only 28 died during rescue and transportation. High lagoon levels and thick vegetation growth prevented Steelhead population censuses in the winter or spring/summer 2017-2018 at the Carmel River Lagoon.[39]

Stakeholders

Various private and public organizations have played a role in the dam removal project. Some of these are:

- California American Water Company (CalAm)

- California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC)

- Monterey Peninsula Water Management District (MPWMD)

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW)

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

- California State Coastal Conservancy

- Rana Creek Ecological Design

- Camp Steffani residents

- Downstream private land owners in Carmel Valley, some of whom have expressed concern that the removal of the dam is increasing flood risk [40]

- CalAm rate payers

- Granite Construction

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 California Water Association. 2019. Fish rebound after San Clemente Dam removed. http://www.calwaterassn.com/fish-rebound-after-san-clemente-dam-removal/

- ↑ Keith Vandevere, Visual Voices Threat of the Dam. Water Over the Dam

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Carmel River Watershed Council, 2010. Carmel River History.

- ↑ Carmel River Watershed Conservancy Home Page.https://www.carmelriverwatershed.org/

- ↑ Active projects in the carmel river watershed. January 2019. Prepared for the Carmel River Watershed Conservancy by Mikaela Bogdan,Gabriela Alberola, Sophia Kirschenman, and Damien Lazzari. https://www.carmelriverwatershed.org/reports.html

- ↑ [CWA] California Water Association. 2019. Fish rebound after San Clemente Dam removed. http://www.calwaterassn.com/fish-rebound-after-san-clemente-dam-removal/

- ↑ Final Supplement to the Environmental Impact Report: San Clemente Dam Seismic Safety Project

- ↑ Resource Conservation District of Monterey County& members of the Carmel River Task Force [1]

- ↑ (USGS) Kapple GW, Mitten HT, Durbin TJ, and Johnson MJ. 1984. Analysis of the Carmel Valley Alluvial Ground-Water Basin, Monterey County, CA, Water-Resources Investigations Report 83-4280.

- ↑ Boughton et al. 2016. Technical memorandum: Removing a dam and re-routing a river: will expected benefits for steelhead be realized in Carmel River, California?.https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1GJd3YXao560rVX2-CX3m65Fary8PxdhB

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1GJd3YXao560rVX2-CX3m65Fary8PxdhB

- ↑ California State Coastal Conservancy. Date unknown. San Clemente Removal Project Description

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 CRRDR PCAP and Monitoring CDFW SAA https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1oDeYj9xuGYBX-qlkcelMoNHcZeskfJ9C]

- ↑ Schmalz D. 2017. High winter flows remade the new Carmel River channel, that might be a good thing. Monterey County Weekly Online.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Harrison LR, East AE, Smith DP, Logan JB, Bond RM, Nicol CL, Williams TH, Boughton DA, Chow K, Luna L. 2018. River response to large-dam removal in a Mediterranean hydroclimatic setting: Carmel River, California, USA: River response to large-dam removal. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 10.1002/esp.4464.

- ↑ DWR Division of Safety Dams. 2012. Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program for the San Clemente Dam Seismic Safety Project.

- ↑ https://www.psmfc.org/steelhead/2016/Urquhart__TUES_PM_SCDRRPFinalCopy4Talk.pdf

- ↑ Smith D., Bogdan, M., Klein J., Terzoli, A., and McNeely S. 2018. Carmel River Reroute and Dam Removal Fish Passage Assessment (Summer 2018). Watershed Institute, California State University Monterey Bay, Publication No. WI-2018-07

- ↑ Smith D., Bogdan, M., Nava, D. 2019. Carmel River Reroute and Dam Removal Fish Passage Assessment (Summer 2019). Watershed Institute, California State University Monterey Bay, Publication No. WI-2019-07, 29 pp.

- ↑ Chow K, Luna L, Delorge A, and Smith D. 2016. 2015 Pre-San Clemente Dam Removal Morphological Monitoring of the Carmel River Channel in Monterey County, California. The Watershed Institute, California State University Monterey Bay, Publication No. WI-2016-01, 50 pp.

- ↑ Steinmetz C. and Smith D. 2018. 2017 Post-San Clemente Dam Removal Morphological Monitoring of the Carmel River Channel in Monterey County, California. The Watershed Institute, California State University Monterey Bay, Publication No. WI-2018-03, 47 pp.

- ↑ Klein J, Bogdan M, Steinmetz C, Kwan-Davis R, Price M, and Smith D. 2019. 2018 Post-San Clemente Dam Removal Morphological Monitoring of the Carmel River Channel in Monterey County, California. The Watershed Institute, California State University Monterey Bay, Publication No. WI-2019-02, 68 pp.

- ↑ Carter L, Fields J, Smith DP. 2016. Large Woody Debris on the Carmel River from Camp Steffani to the Carmel Lagoon, Fall 2015: Watershed Institute, California State University Monterey Bay, Publication No. WI-2016-05, 25 pp.

- ↑ Steinmetz, C. and Smith DP. 2018. Large Woody Debris on the Carmel River from the Former Dam Keeper's House to Carmel Lagoon, Fall 2017: Watershed Institute, California State University Monterey Bay, Publication No. WI-2018-02, 27 pp.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1gltPb-uCmOQ2vxhryRDpEBo2O3MS9zMW

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 PCAP and Monitoring Permits https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1gltPb-uCmOQ2vxhryRDpEBo2O3MS9zMW

- ↑ https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1UTfH1M6vVzKtreVdqEOWxCdxtRFuy9RR

- ↑ SCC_CalAm Agreements https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1jR32VCm-H4e0aMNsp89dr_Lr5PDU9H7H

- ↑ https://drive.google.com/drive/u/0/folders/1GJd3YXao560rVX2-CX3m65Fary8PxdhB

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/environmental-stewardship/mitigation-program/

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Executive-Summary-for-Reporting-Year-2000-2001.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Executive-Summary-for-Reporting-Year-2002-2003.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Executive-Summary-for-Reporting-Year-2003-2004.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Executive-Summary-for-Reporting-Year-2004-2005.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Executive-Summary-for-Reporting-Year-2005-2006.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/MPWMD-Annual-Mitigation-Report-2006-2007.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/MPWMD-Annual-Mitigation-Report-2007-2008.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/programs/mitigation_program/annual_report/2016-2017/MPWMD_MitigationReport_FinalRY2017.pdf

- ↑ https://www.mpwmd.net/wp-content/uploads/MPWMD-MitigationReport-FinalRY2018.pdf

- ↑ https://www.ksbw.com/article/several-homes-flooded-in-the-paso-hondo-neighborhood-in-carmel-valley/26362252

Links

Disclaimer

This page may contain student work completed as part of assigned coursework. It may not be accurate. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of CSUMB, its staff, or students.