Salinas Valley Seawater Intrusion

A watershed-related issue examined by the ENVS 560/L Watershed Systems class at CSUMB.

Contents

Summary

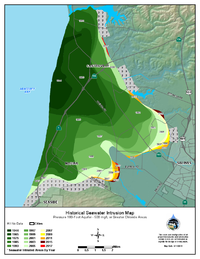

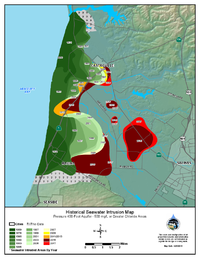

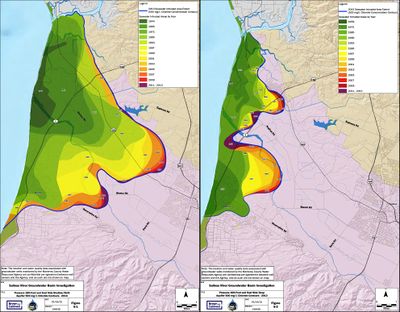

Seawater intrusion into the Salinas Valley aquifers has advanced since it was first measured in 1944.[3] In 2014 elevated salinity levels were recorded less than 1/2 mile from the city of Salinas at the 180-Foot aquifer[4], and seawater at that time was beginning to encroach beyond the limits of Castroville, CA at the 400-Foot aquifer. Current maps from 2018 indicate that these elevated salinity levels may have increased. The extent of seawater intrusion has moved farther inland due to continuing overdraft conditions for municipal and agricultural uses.

Location

The Salinas Valley basin is a groundwater basin beneath the Salinas Valley in California's Central Coast Region and is overseen by the Salinas Valley Basin Groundwater Sustainability Agency (SVBGSA). Groundwater is extracted from four major aquifers: Upper Valley, Forebay, East Side, and Pressure[5]. These aquifers create an interconnected groundwater system that supplies the bulk of the irrigation and municipal water usage in the Salinas Valley.

Hydrology

Along the coast of Monterey County, fresh groundwater flows from inland aquifers to meet with seawater from the ocean. The fresh groundwater flows from the Salinas Valley towards the coast where elevation and groundwater levels are lower. Due to the higher salinity of seawater, it is more dense than fresh groundwater and has a higher hydraulic head. When the fresh groundwater aquifers within the Salinas Valley have a lower hydraulic head, seawater moves inland in a wedge shape under freshwater until head levels return to equilibrium. Seawater and fresh groundwater then mix along the transition zone through dispersion and diffusion, raising salinity levels for wells that tap into these areas.[6] Once seawater intrusion has taken place, the effect on drinking and irrigation water quality within the aquifer is long-lasting. Wells are typically abandoned when salinity exceeds appropriate water quality standards.[7]

Stakeholders

There are a number of key stakeholders invested in groundwater resources such as the agriculture industry, businesses, government agencies, non-profits, and more. The following includes a brief overview of these stakeholder interests:

- The agricultural industry is one key stakeholder within the Salinas Valley, as the estimated worth of the industry is $8.1 billion[8] and depends heavily on groundwater for almost all of its water needs[9]. Irrigation with high-salinity water damages crop yield, crop quality, and soil health for future use of the land for agriculture.[10]

- Water providers in California's Central Coast Region have vested interests in the water management of areas such as Salinas, Castroville and Marina. The residents of these areas rely on the aquifers for urban use. When water salinity rises too high, it becomes unpalatable for drinking water and poses significant health threats.[11]

- The businesses and communities surrounding Lake Nacimiento rely on the lake for recreational use and energy production. The lake is located in both [Monterey County] and the neighboring San Luis Obispo County, and is managed by the Monterey County Water Resources Agency (MCWRA) for the purpose of aquifer recharge and mitigation of saltwater intrusion.

Laws, policies & regulations

Groundwater laws, policies and regulations fall under the regulation of several government entities, including the Monterey County Water Resources Agency (MCWRA) and the Salinas Valley Basin Groundwater Sustainability Agency (SVBGSA).

A special act district, Monterey County Flood Control and Water Conservation District, was formed in 1947 for the Salinas Valley due to early concerns about seawater intrusion and flooding problems throughout the region. In 1991 it became the MCWRA, which monitors groundwater quality and levels[13] but has had little authority in regulating groundwater extraction. On September 16, 2014, Governor Jerry Brown signed into law a three-bill legislative package collectively known as the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). The SGMA mandates the formation of Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSA) and will significantly increase the role and responsibilities of local and state agencies to support sustainable groundwater management. As of March 2016, a draft plan has been developed for the GSA's key actions over the next several years that includes an outline for mitigating seawater intrusion.[14]

Water right laws are important in the management practices of this topic. A water right, as defined by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife is "legal permission to use a reasonable amount of water for a beneficial purpose such as swimming, fishing, farming or industry." [15] Water right laws are administered by the State Water Board's Division of Water Right. [16]

Mitigation Strategies

Seawater intrusion has been, and continues to be, addressed with several mitigation strategies including the implementation and use of dams, recycled water for irrigation, and irrigation efficiency studies and support for growers. Some examples of these strategies are:

- In 1956 the Nacimento Dam and the San Antonio Dam wee constructed for flood control and recharge of the aquifers.

- In 1997 the Monterey Country Reclamation Projects were completed, and include the Salinas Valley Reclamation Project (SVRP) recycled water plant and the Castroville Seawater Intrusion Project (CSIP) distribution system. These projects were designed to retard seawater intrusion and protect drinking water supplies via wastewater recycling at a combined cost of $75 million. [17]

- SVRP treats wastewater to advanced tertiary level. The resultant recycled water meets all California State Standards for recreational and irrigation uses. The facility can produce a maximum of 91 acre-feet per day (29.6 million gallons). It is the largest sewage treatment installation in the world to recycle wastewater for freshly edible food crops.[18]

- CSIP started delivering recycled water to 12,000 acres of farmland near Castroville in 1998. By using recycled water pumped from the Monterey One Water plant, growers safely irrigate their crops and reduce pumping of seawater-intruded groundwater.[18]

- In 2003 the Monterey County Water Resources Agency (MCWRA) joined together with Salinas Valley interest groups to develop the Salinas Valley Water Project (SVWP) to provide long-term management and protection of groundwater resources by stopping seawater intrusion and providing adequate water supplies and flexibility to meet needs in 2030.[19]. To achieve these objectives the SVWP has implemented two projects to date:

- In 2009 the Nacimiento Dam Spillway Modification Component enlarged the original spillway to increase the amount of flood flow that could be controlled by raising and strengthening chute walls and anchoring channel walls. Other modifications included the installation of an Obermeyer (rubber) Gate System and strengthening the bridge pier with steel reinforced concrete.[19]

- The Salinas River Diversion Facility was constructed in 2010 to provide treated (filtered and chlorinated) water from the Salinas River, significantly reducing the need to pump groundwater-except in periods of extremely high demand-through the use of a pneumatically controlled diversion dam.[19]

- Phase II of the Salinas Valley Water Project has been proposed to construct two additional water capture and diversion facilities along the Salinas River. The two water diversion points will be located near Soledad and south of Salinas.[20] As of July 2014, MCWRA had requested resources to conduct an Environmental Impact Report and engaged in initial funding discussions[21].

- Several other irrigation efficiency studies have been and are continuing to help reduce agricultural impact by reducing the quantity of water being applied to crops.[22][23]

Scientific Tools

- The State of the Salinas River Groundwater Basin Report [12] and Groundwater Extraction Summary Report [5], developed by the MCWRA, are useful tools for understanding how groundwater is utilized in the Salinas Valley.

- Monitoring wells at selected sites within the Salinas Valley are tested to assess early indicators of seawater intrusion. Elevated sodium-to-chloride (Na/Cl) ratios indicate that numerous wells on the landward side of the seawater intrusion front have likely been affected, even though the chloride concentration has not increased to the 500 mg/L level used by MCWRA to delineate seawater intrusion.[12]

- Researchers at Stanford University use electrical resistivity tomography to noninvasive image depths of ~490 feet. Monitoring the electrical properties of water salinity along the the coast between Seaside and Marina provides a large area of coverage to map the location of seawater and fresh groundwater.[24]

- The three-dimensional, finite-element-based Integrated Groundwater and Surface-Water Model (IGSM) was originally developed by Dr. Young S. Yoon in 1976 at the University of California, Los Angeles. Designed to simulate confined ground water flow, IGSM later underwent major revisions and modifications[25] including those made during application of IGSM to the Salinas Valley Integrated Groundwater and Surface-Water Model (SVIGSM)[26].

- RMC Water and Environment developed and calibrated an SVIGSM model and applied the criteria to the analysis of alternatives[27].

Ongoing Research

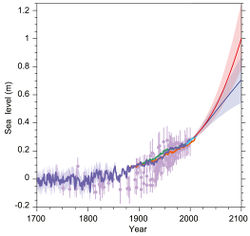

Sea level rise must be included in future coastal aquifer studies due to probable impacts from global climate change. In 2013, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicted about 1 meter of global mean sea level rise that will affect hydraulic head levels and seawater intrusion in Salinas Valley aquifers[28]:

- Research conducted in the Department of Geography at UC Santa Barbara addressed the assessment of seawater intrusion potential from sea level rise in coastal aquifers of California. The Seaside Groundwater Basin, adjacent to the Salinas Valley aquifers, in Monterey County was simulated with sea-level rise of up to 0.9 meters using FEFLOW and ArcGIS as modeling and analytical tools.[29]

Managed aquifer recharge projects provide a method of increasing groundwater supply:

- UC Santa Cruz researchers are involved in a series of studies on managed aquifer recharge using infiltration ponds in central coastal California. They aim to quantify variability in infiltration, recharge, groundwater movement, and water quality. Results suggest that managed recharge systems might be operated for simultaneous improvements to both water supply and quality.[30]

Irrigation management aims to reduce the amount of groundwater extracted for agricultural use and slow the rate of seawater intrusion:

- The Terrestrial Observation and Prediction System (TOPS), a NASA modeling framework developed to monitor and forecast environmental conditions, is being developed to support the use of satellite data to provide rapid assessments of current crop conditions. The TOPS Satellite Irrigation Management Support web interface project will translate the satellite data into formats that are useful to agricultural producers in maximizing irrigation efficiency[31].

- CropManage, a UC Cooperative Extension web application, starting in 2012, began development of evapotranspiration data from the California Irrigation Management and Information System to accurately estimate the appropriate applied irrigation to meet crop needs and minimize potential leaching losses of nitrates. The online interface is directed toward growers to track irrigation and nitrogen fertilizer schedules based on field trials of high-yield production crops.[32]

Groundwater level monitoring provides insight into the quantity of groundwater being extracted within the Salinas Valley:

- MCWRA actively monitors key wells for monthly fluctuations, and annually measures an established network of wells to determine relative changes in groundwater storage. A survey is also conducted each August to monitor changes in coastal groundwater zones that will affect the inland movement of seawater. In addition to these three surveys, the MCWRA maintains a network of dedicated monitoring wells instrumented with electronic data loggers that record data at regular intervals.[33]

Outstanding Concerns

- Seawater continues to contaminate fresh groundwater through inter-aquifer intrusion where vertical transport of seawater in the shallower 180 ft aquifer migrates to the deeper 400 ft aquifer [34].

- In 2017 County Board of Supervisors put forth six recommendations to slow or stop seawater intrusion, including a moratorium on groundwater extractions from new wells [35].

- In February 2018 the Monterey County Board of Supervisors upheld an appeal for permission to install a replacement agricultural well to the deep 900 ft aquifer [36].

- Unregulated drilling and improperly sealed or destroyed wells could be contributing to the problem, and as of 2018 dozens of permits have been given for drilling into the deep aquifer [37].

References

- ↑ Monterey County Water Resources Agency 2017

- ↑ Monterey County Water Resources Agency 2017

- ↑ Bulletin No. 52-B Salinas Basin Investigation Summary Report

- ↑ Historic Seawater Intrusion Map for Pressure 180-Foot Aquifer

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 MCWRA 2015 Summary Report

- ↑ USGS, 1964. Groundwater Resources Program: Saltwater Intrusion https://water.usgs.gov/ogw/gwrp/saltwater/salt.html

- ↑ USGS: Saltwater intrusion in coastal regions of North America

- ↑ MIIS: Agriculture Contributes $8.1 Billion to Local Economy

- ↑ Salinas Valley Water Project Description

- ↑ Pajaro Valley plan targets seawater intrusion

- ↑ NOAA: Can humans drink seawater?

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 State of the Salinas River Groundwater Basin Report (Jan. 2015)

- ↑ Monterey County Water Resources Agency Act

- ↑ California Department of Water Resources: Groundwater Sustainability Program Draft

- ↑ California Department of Fish and Wildlife on Water Rights

- ↑ California State Water Resources Control Board Division of Water Rights - Water Rights Programs Main Page

- ↑ Monterey One Water, 2019. Recycled Water. http://montereyonewater.org/facilities_tertiary_treatment.html

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Marine Coast Water District: Recycled Water

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 MCWRA: Salinas Valley Water Project (SVWP) Overview

- ↑ MCWRA: Salinas Valley Water Project Phase II Overview

- ↑ MCWRA: Salinas Valley Water Project Phase II Project Status

- ↑ Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education: Building Tools and Technical Capacity to Improve Irrigation and Nutrient Management on California's Central Coast

- ↑ UC Cooperative Extension: Irrigation, Water Quality & Water Policy

- ↑ Stanford University: Imaging Saltwater Intrusion Along The Monterey Coast

- ↑ Review of the integrated groundwater and surface-water model (IGSM)

- ↑ MCWRA: Salinas Valley Integrated Ground Water and Surface Model Update

- ↑ Salinas Valley Integrated Regional Water Management Functionally Equivalent Plan Summary Document UPDATE

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 IPCC Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis chapter 13

- ↑ Sea Water Intrusion by Sea-Level Rise: Scenarios for the 21st Century by Hugo A. Loaiciga, Thomas J. Pingel, and Elizabeth S. Garcia

- ↑ California Institute for Water Resources: Improving groundwater recharge

- ↑ TOPS Satellite Irrigation Management Support

- ↑ CropManage Overview: A web application for managing water and nitrogen fertilizer in lettuce

- ↑ MCWRA: Groundwater Level Monitoring Overview

- ↑ Brown and Caldwell. January 2015. State of the Salinas River Groundwater Basin.

- ↑ MCWRA. Expansion of seawater intrusion in the Salinas Valley groundwater basin. Special Report Series 17-01. October 2017.

- ↑ Monterey Herald. Salinas Valley ag well appeal upheld despite worsening seawater intrusion. Jim Johnson. Feb. 2018.

- ↑ Water Deeply. Seawater Intrusion Threatens Some of California’s Richest Farmland. May 2018.

Links

- Other Watershed Issues on the Central Coast of California

- Coastal Retreat in California's Central Coast Region

- Salinas River

- Salinas River Diversion Facility (SRDF)

- Salinas Valley Water Project (SVWP)

- Castroville Seawater Intrusion Project (CSIP)

Disclaimer

This page may contain student work completed as part of assigned coursework. It may not be accurate. It does not necessary reflect the opinion or policy of CSUMB, its staff, or students.