Wildlife Connectivity in California's Central Coast Region

An environmental summary examined by the ENVS 560/L Watershed Systems class at CSUMB.

Contents

Background

Wildlife connectivity refers to the ability of wildlife to move between different habitat patches in a landscape. Landscapes become fragmented when natural land is converted to agriculture or human development, potentially isolating wildlife populations in remaining habitat patches if connectivity is not maintained. Artificial barriers such as roads or fences can also prevent wildlife from safely moving through the landscape.

Connectivity serves a number of purposes for wildlife. Individuals may need to travel between patches to establish breeding territories or find suitable food and shelter. Isolated habitat patches may not be large enough to support viable populations of certain species, potentially leading to local extinction. Isolated populations may also experience higher rates of inbreeding, leading to a lack of genetic diversity and threatening the long-term survival of the population. [1] A lack of connectivity may also diminish the capability of wildlife to provide ecosystem services such as pollination.

Connectivity between habitat patches can be maintained through wildlife corridors, as well as through highway overpasses and underpasses.

Connectivity in the Central Coast Region

Geography

California's Central Coast Region is a mixture of rugged upland habitat interspersed with fertile valleys that have mostly been converted to agriculture. Remaining habitat in the region includes grasslands, oak and conifer woodlands, and chaparral and coastal scrub, with some arid habitat also present but restricted to inland areas. Redwoods can be found in the Big Sur region and in the Santa Cruz mountains.

There are a few significant riparian corridors in the region, including the Salinas, Pajaro, and San Lorenzo rivers. Riparian corridors may function as linkages between fragmented habitat patches, promoting wildlife movement through areas of high human disturbance. [2] Gennet et al. (2013) documented the destruction or degradation of 13.3% of riparian and wetland vegetation along the Salinas River between 2005 and 2009 due to agricultural practices [3]

Notable Wildlife

Many connectivity studies and conservation measures use medium and large mammalian carnivores as the model organism. Mammalian carnivores often have expansive dietary and spatial needs and individuals may need to travel long distances to find mates, and are thus considered appropriate study species for landscape-level connectivity research. Mountain lions, bobcats, and San Joaquin kit foxes are common model organisms in the Central Coast region. San Joaquin kit foxes are considered a Special Status animal in the region and are listed as threatened under the California Endangered Species Act (CESA).

Connectivity is important for migratory species in the region, including birds and bats. Habitat connectivity through corridors and stopover sites provides migratory species with refuge and facilitates movement through disturbed landscapes. [4]

The California Tiger Salamander, a California Special Status species, is also threatened by habitat fragmentation and encroaching development. A 2017 recovery plan from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) determined that preserving and restoring connectivity between upland and aquatic habitat would be a fundamental component of maintaining a viable

Connectivity Studies

A number of studies have been conducted on connectivity priorities in the Central Coast region.

- Thorne et al. 2006: This study evaluated core habitat and connectivity needs for mountain lions and examined the efficacy of using mountain lions as an umbrella species to plan a connected habitat network. [7]

- California Essential Habitat Connectivity Project: The California Department of Transportation (CalTrans) and the CDFW, in collaboration with over 60 organizations, funded a study in 2010 for the statewide assessment of “essential” areas of wildlife connectivity. [8]

- Huber et al. 2010: This study examined potential ecological conservation networks at different spatial scales in the eastern Central Coast region and the Central Valley. [9]

- Bay Area Critical Linkages: The Science and Collaboration for Connected Wildlands (SC Wildlands) used habitat suitability models for an extensive suite of plants and animal species, as well as least-cost corridor analysis for nine mammal species and two bird species, to identify 14 landscape-level habitat corridors that would preserve wildlife connectivity in the Central Coast region [10].

- Huber et al. 2014: This study compiled maps from the four previous studies on wildlife corridors and landscape connectivity for the region and compared them to a habitat suitability model. The results of the habitat suitability model had a significant overlap with maps from the previously conducted studies. [11].

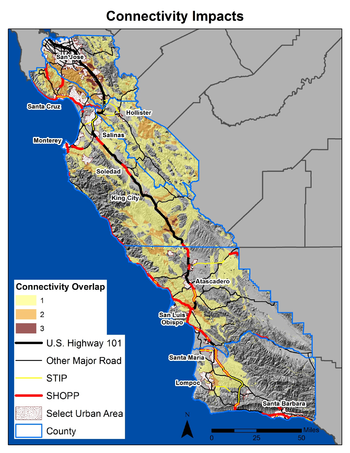

These studies show that connectivity between suitable habitat patches is often impeded in the region's valleys, which have been primarily converted to agriculture and separate remaining natural habitats found in upland areas. Connectivity in low-lying areas is further threatened by growing urbanization, as well as the 38 state and federal highways that cross through the region.

These studies also reveal some of the challenges in establishing connectivity priorities. Due to varying methodologies, including differences in the model organisms studied and the metrics used to quantify fragmentation and connectivity, there were few agreements between these four studies on areas where connectivity should be emphasized. Furthermore, field-based connectivity studies may rely on roadkill surveys or wildlife camera surveys, which are more applicable to large and medium mammals than to small mammals or species from other taxa. Landscape-level habitat linkages that satisfy the connectivity needs of large species may also provide sufficient connectivity for other species, but this is not guaranteed. Certain solutions that focus primarily on increasing connectivity for medium and large mammals, such as enlarging culverts under highways, may have little impact on other species or taxa.

Recent and Current Projects

Projects focused on preserving or restoring wildlife connectivity typically either:

- Establish crossings over or around artificial barriers such as highways. This is often done with wildlife underpasses or enlarged culverts, with wildlife fencing used to discourage animals from crossing elsewhere. Less commonly, wildlife overpasses may be constructed.

- Maintain or create landscape-level habitat linkages. Land trusts and conservancies may purchase land or acquire conservation easements to prevent critical habitat from being developed or to restore degraded habitat and re-establish connectivity. Large-scale projects may involve collaboration among government agencies, NGOs, and universities.

A selection of connectivity projects in California's Central Coast region follows.

Former Fort Ord Habitat Management Plan

The 1997 Habitat Management Plan (HMP) for the former Fort Ord designated land for development or conservation, with an emphasis on protecting habitat for Special Status plants and wildlife such as sand gilia, Monterey spineflower, and Smith's blue butterfly. [13] The HMP identified four conservation areas for Special Status species and proposed a system of three corridors to connect conservation areas. Connectivity may be currently inhibited by roads, such as Reservation Road and Inter-Garrison Road, that intersect the conservation areas without sufficient connectivity infrastructure (i.e. underpasses).

Monterey Coast-Sierra de Salinas Linkage Study

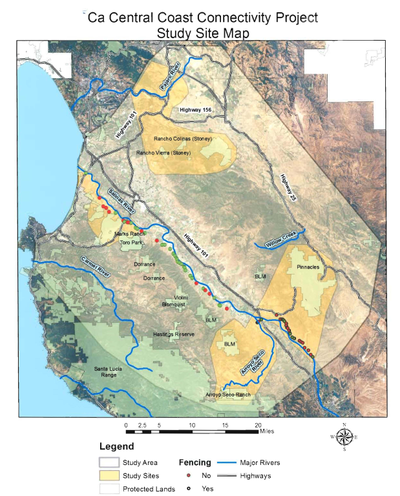

This collaboration between the Big Sur Land Trust (BSLT) and Pathways for Wildlife sought to field-validate the Bay Area Critical Linkages designs between the Gabilan range and the Santa Cruz mountains and from the Coastal Dunes of Monterey to the Sierra de Salinas. [14] Through the use of wildlife cameras, Pathways for Wildlife found that all focal species of the study (bobcat, mountain lion, black-tailed deer, and American badger) were found within areas the Bay Area Critical Linkages project had designated as highly suitable habitat. They also found that wildlife traveled along the riparian corridor of the Salinas River and attempted to travel underneath bridges and culverts to avoid highway crossings. The project documented a mountain lion traveling between Fort Ord National Monument and Marks Ranch via the underpass underneath the El Toro Creek bridge; the Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB) later provided funding to protect this habitat. [15]

Regional Wildlife Corridor and Habitat Connectivity Plan

A 2014 study from CalTrans and the University of California, Davis found that roadwork was slated for many critical areas of connectivity in the Central Coast region. [16] The projects, which included widening existing highways and adding median barriers, were expected to increase wildlife/vehicle collision rates and reduce dispersal capabilities of individuals that could not cross median barriers. CalTrans cited that connectivity was likely already impacted by the roads in these areas, and that additional construction could also allow them to retrofit highways to promote connectivity. Proposed techniques included widening culverts underneath highways and using wildlife fencing to direct individuals to areas of safe passage.

The Pajaro Connectivity Project

The Nature Conservancy launched a project in 2012 to conserve and restore land in the upper Pajaro River floodplain, in part to enhance wildlife connectivity between the Santa Cruz, Diablo, and Gabilan mountain ranges [17]. The project included river corridor restoration on a section of the Pajaro River on the Gonzales Farm, in which more than 1,200 native plants were installed to provide wildlife habitat and facilitate migration and dispersal. Pathways for Wildlife, Sempervirens Fund, Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST), Save the Redwoods League, and the Land Trust of Santa Cruz County were among the collaborators on this project.

The Highway 17 Wildlife Habitat Connectivity Project

The Highway 17 project is a collaborative effort between the Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission (SCCRTC), CalTrans, CDFW, Land Trust of Santa Cruz County, Pathways for Wildlife, and the UCSC Puma Study [18]. Highway 17 is a high-volume highway with concrete median barriers that passes through the Santa Cruz mountains, possibly preventing wildlife from dispersing to areas in the Diablo mountains or farther down the Central Coast region. The project used wildlife cameras, roadkill data, and GPS telemetry data to evaluate possible locations along the highway for infrastructure to facilitate wildlife connectivity, identifying Laurel Curve as the most suitable location. The Land Trust of Santa Cruz County purchased 463 acres of land surrounding Laurel Curve, where a wildlife underpass is currently being planned. [19]

Monterey-Salinas SR 68 Plan

Pathways for Wildlife, at the request of the Transportation Agency for Monterey County (TAMC), used wildlife cameras and roadkill surveys to assess wildlife connectivity across Monterey County's State Route (SR) 68. They identified three priority areas that would reduce vehicle/wildlife collisions and provide connectivity for multiple species, including sensitive species, across SR 68: Portola Drive, the El Toro Creek bridge area, and an area of high wildlife/vehicle collisions near Laguna Seca Golf Ranch. Their primary recommendations included enlarging culverts at all three locations to allow larger-bodied animals to cross under the highway and to provide better visibility for all wildlife, as wildlife are more likely to use culverts that offer a clear line of visibility. These recommendations have been included in a larger SR 68 improvement plan. TAMC estimates that wildlife connectivity sites will be developed within 4-10 years. [20]

Links

- Bat Species of California's Central Coast Region

- Big Sur Land Trust (BSLT)

- California Department of Transportation

- California's Central Coast Region

- Land Trust of Santa Cruz County

- Land Trusts and Conservancies in California's Central Coast Region

- Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and other Non-Profit Organizations in California's Central Coast Region

- Pathways for Wildlife

- Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST)

- Riparian corridors in the California Central Coast Region

- Save the Redwoods League

- Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission (SCCRTC)

- Sempervirens Fund

- Summaries of Environmental Topics on the Central Coast of California

- The Nature Conservancy (TNC)

- Transportation Agency for Monterey County (TAMC)

- Wildlife Corridor

References

- ↑ General information on wildlife connectivity from the Center for Biological Diversity

- ↑ Fremier et al. 2015 journal article: A Riparian Conservation Network for Ecological Resistance

- ↑ Gennet et al. 2013 journal article: Farm practices for food safety: an emerging threat to floodplain and riparian ecosystems

- ↑ Xu et al. 2019 journal article: Loss of functional connectivity in migration networks induces population decline in migratory birds

- ↑ Huber et al. 2014. executive summary: Regional Wildlife Corridor and Habitat Connectivity Plan

- ↑ USFWS and CDFW 2017 Final Recovery Plan for the California Tiger Salamander

- ↑ Thorne et al. 2006 journal article: A Conservation Design for the Central Coast of California and the Evaluation of Mountain Lion as an Umbrella Species

- ↑ CalTrans and CDFW report: California Essential Habitat Connectivity Project

- ↑ Huber et al. 2010 journal article: Spatial scale effects on conservation network design: Trade-offs and omissions in regional versus local scale planning

- ↑ SC Wildlands Connectivity Project List and Descriptions

- ↑ Huber et al. 2014. executive summary: Regional Wildlife Corridor and Habitat Connectivity Plan

- ↑ Final Environmental Impact Report (FEIR): Ferrini Ranch Subdivision. Response from Big Sur Land Trust and Pathways for Wildlife

- ↑ 1997 Fort Ord Habitat Management Plan

- ↑ Report from Pathways for Wildlife on connectivity between the Monterey Coast and the Sierra de Salinas

- ↑ Pathways for Wildlife page on connectivity projects in collaboration with the Big Sur Land Trust

- ↑ CalTrans and UC-Davis Final Report on Regional Wildlife Corridor and Habitat Connectivity Plan

- ↑ TNC site on Pajaro River floodplain restoration

- ↑ Pathways for Wildlife summary on their Highway 17 connectivity research

- ↑ CalTrans presentation on Highway 17 connectivity studies and conservation plans

- ↑ The complete SR 68 Scenic Highway Plan from TAMC

Disclaimer

This page may contain student work completed as part of assigned coursework. It may not be accurate. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of CSUMB, its staff, or students.